If you are a CEO, COO, or business owner, you do not need a 50-page definition of data governance. You need clarity.

At any moment, can you answer, confidently, what your company can do with data safely, consistently, and without risking trust, reputation, or compliance?

That is the practical purpose of data governance.

Data governance is often described as “policies and processes.” That phrasing is technically true and also completely unhelpful. A better way to think about it is this:

Data governance is the operating model that turns business intent into safe, consistent, provable data use.

When governance works, teams move faster because they stop guessing. When it is missing, organizations rely on tribal knowledge and luck. Everything seems fine until one incident makes the hidden fragility visible.

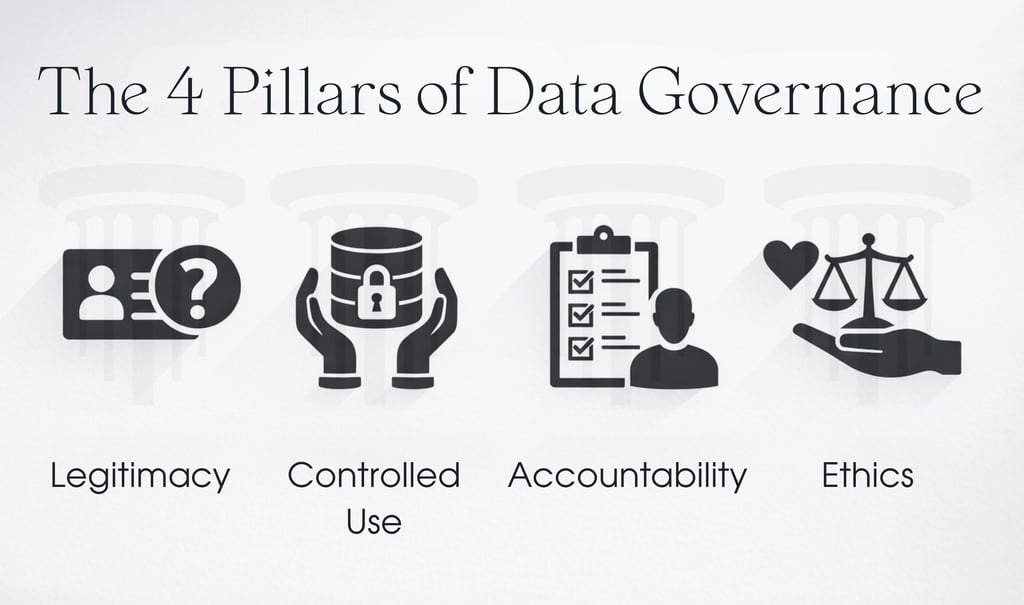

A simple way to make data governance actionable is to treat it as four pillars. If even one pillar is missing, the whole structure becomes shaky.

Pillar 1: Legitimacy

Legitimacy answers a basic question: What data should we collect, and why?

This is about more than legal compliance. It is about discipline. If you collect data you do not need, you create risk, cost, and confusion. You also create the temptation to use it “because it is there.”

Legitimacy usually includes:

Purpose: what the data is for

Scope: what is in and out

Minimization: collect what is needed, not what is possible

Source of truth: where the authoritative record lives

Identifier strategy: how entities are uniquely tracked across systems

This pillar is where many organizations silently sabotage themselves. A classic example is identifiers.

Case study: “Active customer” meant three different things

A mid-sized B2B company had a board dashboard with “Active customers” as a key KPI. It looked stable, until Sales and Finance stopped agreeing on forecasts.

After digging, the definition was different in three places:

Sales meant “customer with an open opportunity in the last 90 days”

Finance meant “customer with paid invoices in the last 12 months”

Operations meant “customer who placed an order in the last 6 months”

No one was wrong, they were just answering different questions with the same label.

The fix was not a new BI tool. It was governance:

decide what “Active customer” means for each business question

name them clearly (for example, Active Customer, Revenue Active Customer, Pipeline Active Customer)

document the logic and owners

bake the definitions into the reporting layer so the debate stops recurring

Lesson: legitimacy starts with meaning. If the business cannot agree on definitions, no amount of dashboards will create clarity.

Pillar 2: Controlled Use

Controlled use answers: How are we allowed to process, share, store, and access data?

This is where security, privacy, retention, and access controls live. But governance is not the same thing as those disciplines.

Security and privacy are what you do. Governance is how you decide, enforce, and prove it consistently across teams.

Controlled use includes:

Access control aligned to real roles, not “everyone in the department”

Auditability, who did what, when, and why

Retention rules, keep what you need, delete what you do not

Data classification, sensitivity and handling rules

Automation, so controls do not depend on people remembering

Case study: shared accounts destroyed auditability

A company had several shared admin accounts used by multiple employees “to save time.” It worked, until something went wrong and nobody could prove who did what.

The result was not just a security issue. It was an accountability collapse:

no reliable audit trail

inability to investigate incidents

increased risk during ISO and compliance audits

uncomfortable leadership conversations that ended in “we cannot prove it either way”

The fix was simple but non-negotiable:

unique accounts

role-based access

audit logs turned on for sensitive actions

a process for privileged access that was fast enough that people did not bypass it

Lesson: if you cannot attribute actions to individuals, you do not have control. You have vibes.

Pillar 3: Accountability

Accountability answers: Who is responsible, and how do we prove what we are doing?

Accountability is not “documentation for the sake of documentation.” It is what makes governance real. It turns intent into evidence.

This pillar is where you build:

Data inventory, what you have and where it lives

Data dictionary, what it means, including edge cases

Ownership model, who is accountable for definitions and risks

Change traceability, what changed, when, and by whom

Issue handling, how data problems are triaged and resolved

A fast diagnostic: Pull One Thread:

Pick a metric and trace it end to end. For example: Units sold.

Ask:

What timeframe are we using, day, week, month?

Is it one plant or all plants? One region or global?

Do we count units when the contract is signed, when it ships, or when it is paid?

What happens with returns, and when does the metric adjust?

What is the source of truth system?

What transformations happen before this shows up in the dashboard?

Who owns the definition and approves changes?

If your team cannot answer these questions, you do not have a reporting issue. You have an accountability gap.

Case study: manual changes with no timestamp:

A company had “quick fixes” being made manually in production, sometimes by developers, sometimes by ops, without a consistent record. When numbers shifted, nobody could explain why.

Leaders experienced it as distrust: “Can we rely on our data or not?”

The fix was governance applied to change:

no manual production changes without logging

changes go through tracked requests, even if lightweight

every change has a timestamp, owner, and reason

critical transformations have versioning so metrics remain comparable over time

Lesson: trust in data is not a feeling. It is traceability.

Pillar 4: Ethics

Ethics answers the question most organizations avoid:

Even if it is legal, is it right?

This is the pillar that keeps governance from becoming “compliance theater.” Ethics is not rigid moralizing. It is a practical promise:

We serve the people whose data we process and the people affected by our decisions. We will not exploit or harm them, even if we could legally get away with it.

Ethics becomes real when it changes how you design systems.

Case study: “Yes, we can send you an Excel”

A company faced new expectations around giving customers access to their data. Their first reaction was, “Sure, we can email an Excel if someone asks.”

That is technically compliant in a narrow sense. It is also strategically hostile:

it does not scale when requests increase

it makes access inconvenient by design

it signals “we will do the minimum, and we hope you do not ask often”

An ethical governance approach reframes the same requirement as trust-building:

create a process that scales, ideally self-serve

define what data is provided, in what format, and within what timeframe

make it usable, not a data dump

treat customer access as a product quality issue, not a legal nuisance

Lesson: ethics is not a constraint that slows you down. It is how you build long-term trust without waiting for a regulator to force your hand.

A common ethics failure: surveillance disguised as governance:

Some companies use “governance” language to justify employee monitoring, productivity scoring, or pressure tactics that have little to do with data safety. That is not governance. That is control masquerading as risk management.

Ethical governance protects freedom where it can, and applies constraints only where there is real risk.

Minimum viable governance in 30 days

You do not need a multi-year program to get real value. A sane 30-day start for most SMEs looks like this:

Data inventory

What data assets exist, where they live, what processes depend on them.Data dictionary

Definitions for key entities and metrics, including edge cases (like returns for “units sold”).Data classification

A practical sensitivity model, plus handling rules that people can follow.RACI

Clear accountability, who is Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed for definitions, access, quality, and changes.

If you add one more thing, make it auditability: unique accounts and logging for sensitive actions. It is hard to overstate how often this is the difference between “we think we are safe” and “we can prove we are safe.”

Why this is not bureaucracy

If you define bureaucracy as pointless paperwork, then governance should not be bureaucracy.

Governance does require structure. So does civil engineering. You do not want a bridge built on improvisation. You also do not want your customer data, financial reporting, and operational decisions running on improvisation.

Governance is the set of guardrails that lets your teams move faster without crashing.

A simple next step

Pick one metric that matters to your business and Pull The Thread. If you cannot trace definition, source, transformations, ownership, and controls, you have found your starting point.

If you want a quick sanity check, book a short call to assess whether your governance is scale-proof and audit-proof, and what the smallest next step is that creates clarity without slowing your teams down.